What is Wuxia?

New to the wuxia genre? By the end of this in-depth guide, you’ll know the basics of the genre as well as some of the most popular themes and tropes that make it awesome.

While people are familiar with Kung Fu, wuxia is relatively new for many audiences.

But wuxia has been around for a VERY long time in Chinese cultures….

THE BASICS

So, what’s this I hear about flying people and swords?

Wuxia is a genre of Chinese fiction that features itinerant warriors of extreme (almost supernatural) martial arts skill in ancient China. These aren’t your average heroes. We’re talking people that can fly through the trees, cross vast distances in a single leap, reverse the flow of blood in the body with internal qi, and other amazing, superhuman feats. They travel around righting wrongs, helping people, and being good guys.

That’s the short answer.

Ready for more?

As a genre, wuxia is a major part of pop culture in Chinese speaking communities around the world—kind of like the way superhero stories are in western countries. In fact, one of the most popular series of the 20th century, The Legend of the Condor Heroes, is considered to have the same kind of cultural impact in Asia that Lord of the Rings and Star Wars had in the west.

That’s a big deal.

But funny enough, this genre hasn’t really translated that well into English—Condor Heroes was only recently translated into English. Because the genre often takes places in well-defined historical settings, the tropes and conventions of the genre can make it hard to accept. My theory is that there’s a suspension of disbelief that might feel a bit far for western audiences. Somehow martial artists fighting in the air over a lake is less believable than a superhero that can fly with a hammer. There might also be a bit of cultural unfamiliarity here at play—when something is too foreign it’s easier to reject it than to try to understand it.

Because there isn’t a ton of wuxia stories in English, I’ve chosen to write in this genre. I love these stories. My Chinese reading wasn’t great as a kid, and I couldn’t read these stories in Chinese. I’m writing these stories in English for the kids of the diaspora, for kids like me that wanted to experience these adventures but couldn’t get through the language barrier.

Yes, this is a perfectly fine place to have a duel.

(Source: Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon)

What kind of medium are wuxia stories told in?

While in the west, it’s most common for people to interact with this genre through movies (Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, Hero, Kung Fu Panda, Disney’s Mulan), the genre has its origin in books and oral stories and has been around for more than 2000 YEARS. Today you’ll find wuxia stories in books, novels, movies, comics (manhua, manga, manhwa), video games, mobile games, opera, and more.

Wuxia webnovels and webtoons are particularly popular in the genre today, and there are a growing number of wuxia stories in the LitRPG genre as well. Wuxia stories aren’t quite as popular as samurai stories, but we’re hoping to change that, aren’t we?

How does Wuxia differ from Kung Fu?

While the two are quite similar in their portrayals of martial arts, wuxia tends to lean on the fantastical, supernatural, mystical end of martial arts. The fighters in wuxia movies specialize in weapons, both traditional and strange. Wuxia movies have ancient Chinese settings, and fighters are often warriors of the jianghu.

Kung Fu stories, on the other hand, tend to focus more on unarmed combat, though they often have improvised weapons (see Jackie Chan), or non-lethal weapons. Kung Fu stories are usually set in the modern era or the 19th and 20th century. The fighting in these stories tend to be more realistic—you could see something like it happening.

What does wuxia

(武俠) mean? How do you pronounce it?

Wuxia literally means martial (武) and hero(俠). But Martial Heroes doesn’t really capture the jaw-dropping awe of the genre. If you read Mandarin Pinyin, then it’s wǔxiá (3rd tone, 2nd tone). If you don’t read Pinyin, you’d say it like woo + shee-ah.

What is wu (武)?

The wu part means martial, military, or armed. This is the same wu you find in wushu (martial arts). This character is made up of the foot radical, and the spear radical, giving the idea that it’s an army going on an expedition. There’s a story about the graphical origin of 武 as “to stop violence” – the ultimate state of just warfare.

‘The Viscount of Chu said, “You do not understand. In writing, the characters ‘to stop’ and ‘halberd’ combine into ‘martial virtue’.”

The idea here of ending violence is central to a lot of wuxia stories. But we’ll get to that in a minute.

One thing that’s often talked about in this genre is someone’s wugong (武功), or your martial skill. For those of you that might recognize the gong, that gong is the same as “kung” fu (oh how complicated it gets with all the different translation forms). Fun fact—you can use the phrase kung fu in Chinese to apply to anything that requires skill.

Cooking? Kung Fu.

Driving? Kung Fu.

Washing the dishes? Sure if you want. Kung Fu.

A power fantasy

Wuxia heroes are always seeking to improve their martial arts abilities and to test themselves against other opponents. After all, they are MARTIAL heroes. Their martial arts skills are an integral part of their identity. Because of this, there are rivalries between schools and sects and disputes are settled in duels and arranged fights.

What is Xia (俠) and the Code of the Xia?

Xia is where this gets a bit complicated—it’s hard to find a good translation of the word in English. Xia means chivalrous, vigilante, or hero. Xia has its origins in the Chinese version of knight-errantry, and in some ways, a xia is like a knight. A xia is someone that is chivalrous and bound by a moral code of conduct. Sometimes this ethical code of conduct might bring them into conflict with the actual laws of the land and whatever government may be in place.

In this light, a martial artist follows the code of xia and is a xia as well. The xia don’t belong to any noble lord, typically shun, military power. They generally come from the lower social classes of ancient Chinese society. They are both male and female.

If you’re familiar with the Japanese samurai bushido (武士道) in stories, you’ll notice a few similarities here. You might also see some similarities with Robin Hood if you’re coming over from a Western perspective. The xia often helps the oppressed.

In short: a xia is an honorable person that uses their considerable martial art skills for good rather than any kind of personal gain.

The Code of the Xia

The code is incredibly important to the genre—it’s the core morality (and mentality) of every xia hero. This code of chivalry and righteousness guides the actions of the heroes. It sends them into situations where they must rely on themselves and their system to right the wrongs of the oppressed, to fight against injustice, remove oppressor, and seek retribution for transgressions. In a lot of ways, it’s similar to the modern concept of the origin story to a superhero.

Two main concepts central to the code of the xia are honor and righteousness. These two concepts govern the way heroes behave. It emphasizes the need to repay acts of kindness (ēn恩), and violence and vengeance (仇chóu) to bring villains to justice. Adherence to the code and the interpretation of it is what causes the heroes to kill or die, even passing on grudges and quests from generation to generation until vengeance is achieved or honor is restored.

The world of wuxia is one where your word is your bond. Because your honor is dependent on the words you say and the actions you take, any oath that a hero makes is significant. There are few worse sins in the wuxia world than breaking your oath. Swearing an oath of brotherhood is a serious undertaking, the most popular of which would be the Oath of the Peach Garden in the Romance of the Three Kingdoms.

The famous oath. I think they got roaring drunk after.

Let’s look at how oaths and honor can work in an example:

Hero X may swear an oath of brotherhood to hero Y for saving their life. X will always be a friend to Y and will help Y out of future problems they may encounter. If Y should fall in combat, X may take it upon themselves to avenge Y’s death. If he fails in the attempt, X might pass the quest for revenge on to his son.

There are eight more common attributes that make up the code of the xia:

Benevolence (仁)

Justice

Individualism

Loyalty (忠)

Courage (勇)

Truthfulness

Disregard for wealth

Because these attributes are important, it’s often quite easy to spot a villain in wuxia stories—they are not honorable and will lack some of these attributes. In many cases, they will be traitors, cowards, greedy, and or cruel.

Obey your master

How it feels when I’m writing. (Source: Snake in the Eagle’s Shadow)

As part of the xia code, martial heroes are expected to be loyal to their masters (shifu) and obey them in all things—After all, their skills and abilities have to come from somewhere. In wuxia stories, it is quite common to see a young person, hoping to learn some martial skill, beg at the feet of a person to take them on as a disciple. Sometimes the young person will be rejected or will have to prove their worthiness by performing some kind of task.

The master/disciple relationship has deep roots in Confucian relations and mimics the way family trees are established. A master may have ten disciples, and their ranks will be determined by their age, the most senior having the most say. With the master at the head, the disciples become brothers and sisters. This pecking order is a little bit different from the idea of sworn brothers and sisters, and we’ll get into that later.

A master also may be killed to provoke the protagonist in the story. Because of Confucian principles, this is often a compelling motivator.

Settling a dispute according to the code of Xia

Well, if you’re a martial hero with unsurpassed skill, and I’m a martial hero with unmatched ability, and we offend each other, the honorable way to settle our dispute is through a duel. Some of these duels may be to first blood, critical hit, or even the death. Some of these duels can be very public affairs, drawing in observers from all corners of the martial world, while others may be private affairs—a duel in the night on the peak of a lonely mountain.

SETTING AND TROPES

What kind of settings do wuxia stories have?

Though Wuxia stories are set in “ancient China,” Wuxia is not bound to any particular dynasty. Generally speaking, wuxia stories find their settings in ancient or pre-modern China. In some stories, like Legend of the Condor Heroes, the period and dynasty play an essential part of the story. However, in many other stories, ancient China is just the backdrop, and the world the story takes place in is something you could call “China-inspired.”

The most crucial element to a wuxia tale is the martial arts. The characters involved must know martial arts. Without martial arts, the story would just be a piece of historical fiction. Martial arts schools, sects, temples, are pervasive settings.

That said, some of these stories have a fantasy or supernatural element as well. Characters can use magical powers, fight supernatural creatures, monsters and demons, or even exist in entirely fantasy settings. Modern wuxia stories sometimes take place in modern times or have characters that are transported from contemporary settings into ancient settings (or the other way round as well), or reincarnated into a video game. Regardless of how it happens, martial arts is the key.

What are Jianghu (江湖)

and Wulin (武林)?

The term jianghu means rivers and lakes but mainly refers to the setting of a wuxia story—the martial arts world of ancient China. It’s a subculture of martial artists, merchants, beggars, vagabonds, bandits, outlaws, gangs, craftsman, musicians, adventurers, and rebels. While the imperial court may rule an empire from above, the jianghu is the underside of the empire, the underworld that runs in parallel.

The jianghu has its code of honor that runs close to the code of the xia. Generally, a common aspect of the jianghu setting is that the standard law and order of the land are corrupt, and disputes must be settled by men and women of honor, all members of the jianghu community. It’s a lot like the Wild West, where people take the law into their own hands.

The wulin translates literally to “martial forest” and refers specifically to the world of martial artists.

“He is the most powerful man in the jianghu” = Someone that could be influential and has lots of connections and wealth. Maybe he has an army of thugs. He might not even know martial arts.

“She is the most powerful woman in the wulin” = Someone that is a super scary and dangerous martial artist.

What kind of themes are there in wuxia stories?

In all reality, you can find all of the typical narrative themes in wuxia. Love, life, and death can all be found here. The narrative in traditional wuxia stories follow themes of loyalty, family, brotherhood, justice, courage, and all of the attributes of the xia code. Romance is a given, as is betrayal. These themes tend to act as a basis for wuxia stories. How each story approaches these concepts makes for unique and exciting tales. Every storyteller likes to weave multiple themes together in their tales, creating layers of thematic nuance.

It’s about justice

Perhaps the most common wuxia theme is justice because of the code of the xia. As a do-gooder, the martial hero will generally be found wandering around looking for wrongs to right, the unfortunate to save, and the wicked to punish.

In that light, redemption, and revenge are prevalent themes found in wuxia stories. Whether it’s avenging the death of a friend, family member, or master, revenge is often a powerful motivator in wuxia stories. Vengeance, the need to punish wrong deeds, ties back into the need for justice in the xia code.

Patriotism and nationalistic pride also appear in wuxia stories (as seen in Condor Heroes), as well as crime and mystery. It seems that everyone loves a good whodunnit.

Coming of age

A typical story revolves around a young protagonist that experiences personal tragedy before setting off on an adventure to learn multiple forms of martial arts from different masters. Through overcoming strict training, trials, and other tribulations, they become a peerless fighter of great power—often becoming the most powerful fighter in the jianghu.

A classic example of this story is Legend of the Condor Heroes. Guo Jing is a bit of a moron. His father was killed before he was born. But eventually, Guo Jing goes on to learn martial arts from nearly all of the greatest martial artists in China. How you get that lucky is beyond me.

Dedication

Some stories revolve around a protagonist that is ridiculed and abused by others, but trains in secret (taught by a powerful master that takes pity on them). They may beg and plead for the master to teach them, showing their dedication by waiting in the cold and rain for days on end or performing menial tasks to prove their devotion. Eventually, they earn the master’s approval and learn from them, developing the skills to surprise/defeat those that initially looked down on them.

Defeat your arch-nemesis

After all the training, it’s time for the apprentice to defeat his arch-nemesis. Sometimes this means defeating a fellow student turned rogue, or the master’s long time rival. Whatever the case, it’s always a battle between powerful enemies in a dramatic showdown.

Anime and Manga Influences

If you think that there’s a lot of similarity between wuxia and shōnen manga and anime, you’re on to something. Stories like Dragonball, Naruto, My Hero Academia, Fate/Stay are all about coming of age, powering up, learning to be the greatest fighter of all time, and defeating their arch-nemesis. That’s not to say that they’re directly related, but these days stories draw thematic inspiration from each other all the time. We live in a beautiful cross-culture blender.

Tropes you might see in a wuxia story

Martial arts skills and abilities

Oh boy, now we’re into the fun stuff. The martial arts in wuxia stories are often based on real-world martial arts, and sometimes these schools (Wudang, Shaolin, Emei) make their appearance in wuxia stories. But in fiction, the real highlights of a wuxia story is the crazy abilities, techniques, and weapons that people use. Here’s a breakdown of what these things are:

Martial Arts and Weapons

Every school/sect of the wulin has some kind of secret technique that is their claim to fame. Often these revolve around a particular weapon type or fighting style. They usually have ridiculously awesome names too:

White camel Mountain Manor

Iron Palm Sect

Villain’s Valley

Twelve Linked Fortress

Jade Sword Manor

Five Dragons Gang

Heaven Demon’s Cult

Every school has some kind of legendary technique or move. Often, it’s an equally ridiculous/awesome name. You want more fun? Check out this random martial art move name generator. The righteous uppercut of the mice? Endless fun.

But the weapons! Oh, the weapons.

I’ll be honest; the weapons were what drew me to the genre as a kid. They still fascinate me. These weapons, in some ways, act as a character’s defining trait—no need for further character development. Fighters in a wuxia story use everything as a weapon. I mean EVERYTHING.

But wait! There’s more!

First the standard weapons of martial arts: the jian (straight sword), dao (broadsword or saber), qiang (spear) and gun (staff). Then we get the more exotic stuff: meteor hammers, rope darts, knives, hook swords, maces, halberds, ring swords, tonfa, sickles, and axes.

Yes, that is a parasol made of blades. Yes, he’s about to kick some ass with it.

(Source: Shadow, 2018)

Then comes the really bizarre/fun stuff—Fans, ink brushes, sewing needles, throwing needles, musical instruments, boat oars, abacus, parasols, weighing scales, benches (!) and more.

Like I said, bizarre and awesome.

Qinggong (Lightness Kung Fu)

Nothing like a little stroll on the lake. (Source: Hero, 2002)

You’ve probably seen the wuxia jumps where the hero (or villain) goes leaping high into the trees, or up onto the roof of a building. It’s not a type of jump as much as it is an entire school of wugong or martial technique. This is qinggong. I’ve seen this translated as “lightness” kung fu, which makes sense. Qinggong is, obviously, super exaggerated, but the real world qinggong is closer in execution to modern-day free-running/parkour than flying through the air.

Still, qinggong is a super fun part of wuxia stories. Funny enough, this is where some western audiences draw the line in their suspension of disbelief.

Neili/Neigong (Internal strength)

This is also a good place to meditate. (Source: Cultural-China.com)

If you’ve read a wuxia story, or seen a kung fu movie, you might be wondering why wuxia characters are always cultivating their qi in the mountains through deep meditation. That’s because they’re cultivating their inner energy and building up their reserve of power and strength.

Qi is the inner energy that has real-world origins. Millions of people around the world practice some form of qigong for health and wellness. In fiction, this qi can be used for attack and defensive techniques. Manipulation of qi is what gives wuxia heroes (and villains) the abilities to use qinggong, develop superhuman speed, strength, stamina, or durability, as well as heal rapidly.

Some examples:

Hero X gets struck by a poison needle. His neigong is really strong, so he uses his qi to expel the poison from his body.

Hero Y uses her qi to strengthen the thickness of her skin, making her immune to weapons.

Hero Z has massive qi reserves and has very strong neigong. When she fights, regular attacks don’t phase her at all.

Dianxue (Touching pressure points)

Another hallmark of wuxia stories is the use of acupuncture techniques against opponents. Characters will strike different pressure points on the body to paralyze their opponents, kill them, or even drain their power.

On the other side of the equation, striking the acupuncture points can be used to heal as well, allowing the body to halt bleeding, expel poison, enter sleeping/meditative trances.

Secret Manuals

Read the instructions! Every martial arts school has a manual that details how to master their technique—sometimes at a greatly accelerated rate. This is part of how techniques are passed down from generation to generation. Secret manuals contain all kinds of secrets—dark truths from the distant past of the school, the origins of the technique that the school wants no one to learn.

The teachings in these manuals are often the very peak of martial skill—teachings that masters only keep to themselves or prized pupils. While there may be many practitioners of their particular brand of martial arts, only the very elite will have access to the secrets in the manual, and therefore the highest tier of mastery and power.

These manuals are also a giant McGuffin in wuxia stories—the object that serves a trigger for the plot. Usually, it’s because the secret manual has been stolen, and now there is an all-out war between sects to recover it.

And now, a very brief guide to tropes in wuxia stories

There are a ton, but I’m going to cover a few of the more popular ones.

The oath of brotherhood

Even though this is considered a trope, it’s also based on real-world customs. In wuxia stories, characters that are not related by birth will swear an oath of brotherhood (or sisterhood) and continue on their adventures together. It’s the highest bond of loyalty, and there are times where it surpasses actual familial ties. I guess your found family is better than your real family sometimes in ancient China too.

Making the oath of brotherhood is done through ritual. Sometimes this is done in dramatic settings (the top of a mountain at dawn) or casual settings (the local pub). Perhaps the most popular example of this is the Peach Garden Oath in The Romance of the Three Kingdoms. Liu Bei, Guan Yu, and Zhang Fei all swear to be brothers and die on the same day. This bond of brotherhood is so strong between these characters that it leads them to act from high moral ground and make catastrophically bad decisions. This oath of brotherhood is one of the reasons why Guan Yu is prayed to by criminals and law enforcement officials alike—he is a paragon of loyalty.

You don’t get a statue this huge unless you’re a big deal.

Betrayal!

Breaking the oath of brotherhood is a massive and heartbreaking thing that can lead to great stories because of the emotion involved with such an action. While that’s one way to betray the protagonist in a story, wuxia often features apprentices and disciples that scheme against the master, a student that could have been a real star (if not for the darkness in their heart).

Everyone can be a fighter

One thing I love about these stories is how fighting and martial skill is not gender bound like in some other genres. In wuxia, men and women can both attain insane levels of skill. This isn’t just a modern convention either—there is evidence of female protagonists in wuxia stories dating back as far as the 7th century Tang dynasty. There are probably stories even older than that as well.

This gender equality in the martial world also lends itself to creating literal “power couples.” Protagonists are attracted to each other not only because of their beauty (or the power of being the male and female lead) but also because their wugong is particularly powerful.

Train, train, train, train…or don’t

If there’s anything that a wuxia story likes, its training montages. The skills of its characters are often the result of years and years and years of training, usually under the tutelage of a harsh (sometimes doting) master. The genre likes to flip this on its head as well by introducing the prodigy that can learn everything very quickly. Usually, this prodigy isn’t even aware that they are a prodigy.

Related to this are the hazards of being a master. If you’re good, you’re at the top. If you’re at the top, you’re going to be challenged. Rivals will come out of the woodwork to challenge a master in a wuxia story. When a pupil has learned all there is to learn, a master may simply declare that they are done and vanish into the night. Alternatively, a master may be killed to provoke the protagonist in the story. Because of Confucian principles, this is often a compelling motivator.

Hide your talents

Not everything is as it appears in the jianghu. One of the most famous sects across authors and mediums is the Beggar Sect. They’re beggars and hobos that roam the land. But they’re also really good at fighting and form a massive spy network. The chief of the beggar clan is often a master of unmatched skill.

Because Asian culture emphasizes respect to the elderly, the elderly shifu is often a powerful martial hero. These characters often cross paths with the protagonists, testing them to determine if they are righteous or not before passing on their skills.

The movie Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon is about hiding your talents. Jen Yu is a nobleman’s daughter on her way to get married. She’s also a powerful fighter. Hiding your skills is a common trope.

Single-minded obsession

Because protagonists in wuxia stories are motivated by justice and increasing their skill, they often become ultimately and obsessed with their quest. Whether it’s because they need to punish a misdeed (you killed my master!) or because they have to defeat a rival (I will become stronger and beat you!) this obsession can overtake all aspects of their life. In some cases, this turns them into an Ahab-like character whose obsession will ultimately be their downfall.

For a full list of tropes, check out TV Tropes’ great list. Wow. It’s really good.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF WUXIA

Though the name wuxia is relatively modern, stories of the xia are really old. This genre is old, and I mean ANCIENT. We’re talking 2nd or 3rd century BCE old. Some of the first stories wuxia stories originated as far back as the unification (pacification?) of China under Qin Shi Huang, the first emperor of China. If you’ve seen the movie Hero, you’ve seen a retelling of one of the oldest wuxia stories around.

The first form of these stories are about wanderers (youxia游俠) and assassins (cike 刺客). Xiake stories—as they were known as—were popular stories and legends. In the Records of the Grand Historian, Sima Qian mentions five assassins that undertook tasks of political assassinations of aristocrats and nobles. During this period, assassination was seen as a noble act as it was done out of loyalty and honor. These types of stories would later be documented in historical books like The Book of the Han.

Xiake stories made a comeback in the Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE) and were then called chuanqi (傳奇) or legendary tales. It was in this time the prototype for the modern wuxia story was born. Stories from that era like Nie Yinnaing, and the Kunlun Slave, have settings and themes, as well as heroic deeds, that you might find in modern wuxia stories.

During the Tang dynasty, the military romance/epic was also developed but came to fruition in the Ming Dynasty when Luo Guanzhong wrote the Romance of the Three Kingdoms. Though Three Kingdoms isn’t considered a wuxia story, it does draw on wuxia elements and has detailed descriptions of fighting that would be emulated by wuxia writers. Three Kingdoms is regarded as one of the Four Great Classical Novels of Chinese literature.

During this period, Shi Nai’an wrote the Water Margin, another classic of Chinese literature. This story is perhaps the first full-length wuxia novel. It portrays the deplorable socioeconomic circumstances of the late Northern Song dynasty and the emergence of 108 heroes that fought to make things better. They followed a code of honor and became outlaws rather than to serve corrupt governments. This story is also seen as a precursor to the concept of the jianghu that would later emerge in the genre.

Many novels and stories from the Ming and the Qing dynasties were lost because of government prohibition. At the time, stories of freedom and fighting were deemed as seditious in times of peace. Government officials blamed growing rebellions on these stories (rather than their corrupt practices or injustice…go figure). Yet the genre lived on and evolved, giving birth to gongan (public case) detective stories. In these stories, a judge or magistrate solved crimes and battled corruption and injustice. Justice Bao is the most famous of these stories, and his stories are made into movies and TV shows today.

The modern era of wuxia really began in the 20th century, first as a desire to break with Confucian values. The xia emerged as a symbol of personal freedom, defiance of tradition, and rejection of the ancient family system. While these stories would be banned from time to time, wuxia stories began to proliferate in other Chinese speaking areas like Taiwan and Hong Kong. Writers like Louis Cha (Jin Yong) and Liang Yusheng, wrote serials for newspapers and magazines (serials like this still exist today, though in the form of webtoons and other series). Other famous writers include Gu Long, Huang Yi, Wen Rulan, Sima Ziyan.

With the onset of TV and film, these stories have made the jump into different medium. Though the earliest films date back to the 1920s, the Shaw Studio in Hong Kong were pioneers of the modern version of this genre. They combined stunning choreography and brought qinggong to life with wire-assisted action and trampolines.

Wuxia made its first big splash in 2000 with Ang Lee’s Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon. This movie was a surprise to audiences in and out of Asia. For those outside of Asia, it was their introduction to the wonder and beauty of the genre. For those in Asia, it was another wuxia film (so what’s the big deal—my auntie said). Since then more and more wuxia type films have made their way over to the west, and more and more TV shows, after airing in the East, will debut in the west. The age of streaming makes it easier for audiences around the world to access the genre.

The genre now is filled with stories by aspiring authors from around the world—yours truly included.

WHERE TO START WITH WUXIA

Now that you know all about the genre, what books or movies should you check out?

The first starting place for you, I think, is a movie. Wuxia is a genre that thrives on great visuals. Here are my top three choices of great classic wuxia movies.

HERO - Starring Jet Li, Tony Leung, and Maggie Cheung, Donnie Yen, and Zhang Ziyi, this is one movie I personally revisit every single year, sometimes even once a quarter. The visuals are absolutely astounding, and the martial arts involved is breathtaking.

CROUCHING TIGER HIDDEN DRAGON - In the early 2000s, the west fell in love with this movie. It’s easy to see why — this is peak Michelle Yeoh and Zhang Ziyi. The fight sequences are absolutely stunning and it really showcases a lot of the tropes included in this article. From the setting to the heartbreaking soundtrack, this movie is one of my all-time favorites.

The Five Deadly Venoms - A classic kung fu movie, this movie has a lot of wuxia elements and is an iconic martial arts film. It’s a story of secret identities and redemption, brotherhood … and murder. It showcases different styles of fighting, and focuses on many of the themes that makes a great wuxia story.

Of course, you could just jump right into some books too! I highly recommend THE LEGEND OF THE CONDOR HEROES by Jin Yong. As said earlier, it had the same sort of cultural impact in the east as Star Wars and LOTR. It’s a big deal.

Beyond that, how about a couple of my books? ;)

WUXIA BOOKS BY JF LEE

-

TALES OF THE SWORDSMAN

Shu Yan will not be sold again. But with bounty hunters from the wulin on her tail, is the company of a legendary swordsman bent on revenge really the safest option? Combining martial arts action, witty banter, and LOL humor, this wuxia epic is inspired by anime, the MCU, and of course, lots and lots of swords.

-

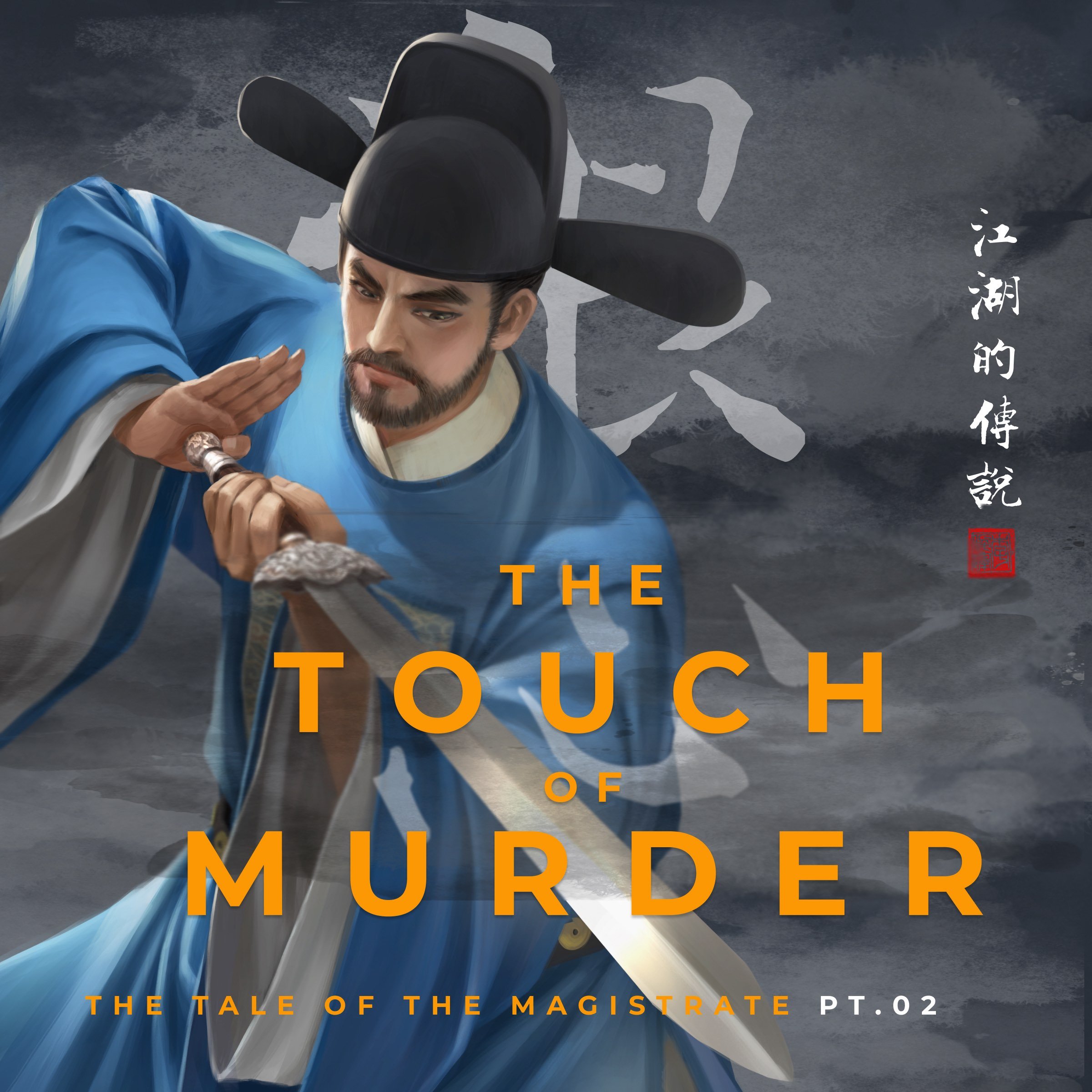

THE TALE OF THE MAGISTRATE

This series is a detective story with wuxia action follows beloved (and totally corrupt) Magistrate Tao Jun and his dry and irreverent take on the jianghu and the bureaucracy of being a magistrate. Well, dodging archers' arrows is more fun than paperwork anyway.

-

TALES FROM THE JIANGHU

Yan Tao's daily routine as the proprietor of the Green Brocade Inn is similar to most other proprietors: manage the books, order ingredients, train the staff, and greet guests. But when a group of bandits appears, the fate of his inn rests in the hands of a young pugilist with a mysterious past.